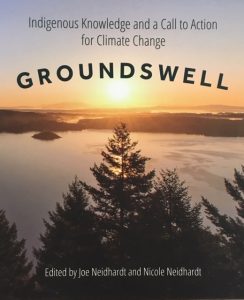

Groundswell: Indigenous Knowledge and A Call to Action for Climate Change, Joe Neidhardt & Nicole Neidhardt, Eds. (2018)

This collection of accounts of how Indigenous people, many of them Dine’ ( Navajo), experience and are addressing the growing crisis of climate change is not only enlightening for non-Native readers. It is also a passionate exhortation to wake up, to accept that we who are descendants of the original White colonists of the American continent may not know everything we think we do (despite our our PhDs, our much-vaunted “science,” and our theoretically superior form of government). We—who have everything to gain, nothing to lose, and a great deal to learn in a very little time—may actually be able to learn it from those who have lived in harmony with Nature on Turtle Island for thousands of years.

Early European settlers were welcomed to this continent by its original inhabitants, and in the beginning all went well. The newcomers had enough sense to realize they knew nothing about this land and were therefore utterly dependent upon the wisdom and guidance of its First People. Then some among them became inspired by the Catholic Church’s Doctrine of Discovery, which held that since only landed White Europeans were actually human and anyone else was an animal, those “non-humans” could be exploited and even killed with no stain on the souls of the murderers, and their land and all their possessions could be confiscated for the Church. Urged on by their own greed and that of numerous European monarchs, these ungrateful guests decided to take matters into their own hands, to ignore the Native teachings, and to seek to acquire more land, more goods, and worst of all, slaves to do the heavy lifting. They turned their backs on the obvious wisdom of Indigenous communal lifeways and spread out across the continent, brutalizing, enslaving, and murdering their hosts and leaving wreckage and disease behind them as they went.

Whether we wish to acknowledge it or not, the ongoing fallout from this capitalistic philosophy is the mess we’re all experiencing today—Native and non-Native alike.

As a mother, I couldn’t help but notice a gentle note of parental reprimand in some of these accounts. But I have yet to read a word of actual blame, though Western European thought is, if not to blame, at least a major catalyst in this sad state of affairs. Instead, I’m humbled to find that many of the older contributors to the Neidhardts’ anthology see the “settlers” as uninformed and undisciplined children, in need of patient education by the adults around them. I was particularly touched by the thoughts of some of the younger authors, who refuse to be disheartened by the current turn of events and are instead creating movements and educational opportunities that will benefit all who are willing to participate in this groundswell of decolonization. These young leaders remind us that we were all indigenous to the land somewhere, in some time, and that it’s only Western society’s fast-paced acquisitive way of life that has caused us to forget.

The writing in Groundswell is thought-provoking and inspiring, the artwork and photography breathtaking. Most importantly, the sense of care, forgiveness, and determination to share life-saving wisdom, to persist in spite of the odds, that permeates these pages gives me hope that one day—if not in my lifetime or perhaps even that of my children or grandchildren, but certainly seven generations down the road—we will walk together in Beauty on Turtle Island, in harmony with Nature and all her creatures.

Reviewed by Valentine McKay-Riddell, PhD